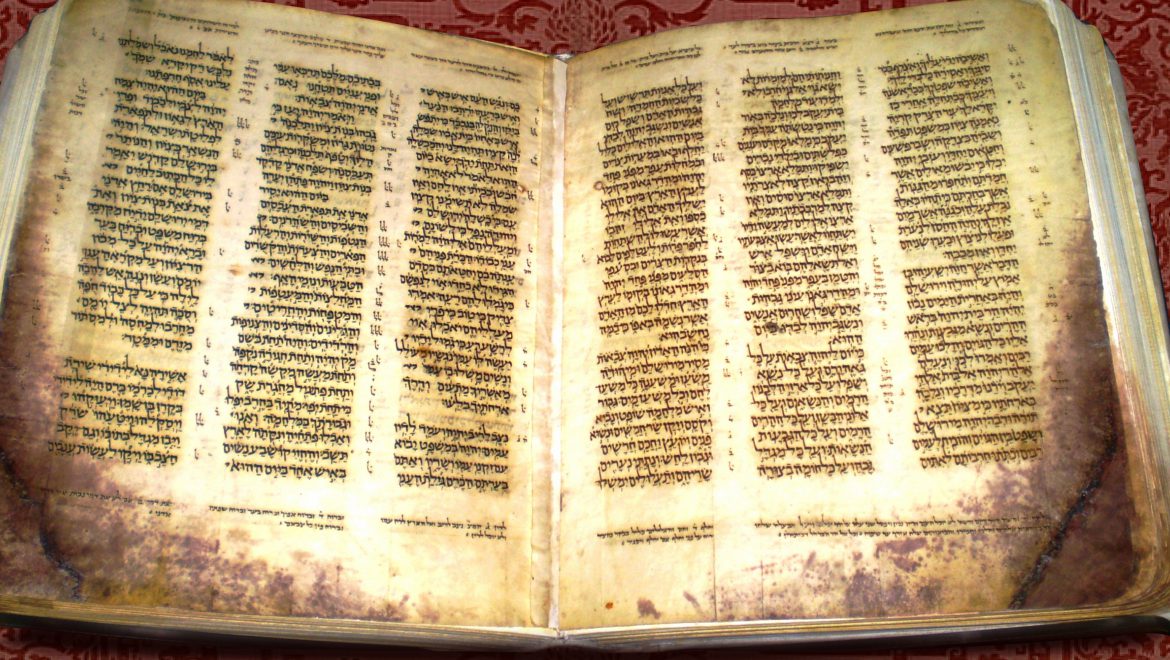

This thorough article by Rabbi Yizchak Etshalom outlines the structure of the Grace After Meals, explaining how the Biblical command to thank God for the food and land is fulfilled through this lengthy prayer, written by multiple authors throughout Jewish history. This historical approach is most relevant to those with an interest in the development of Jewish liturgy. Rabbi Yizchak Etshalom is the Educational Coordinator of the Jewish Studies Institute of the Yeshiva of Los Angeles.

The Composition Of Birkat Hamazon

So, what is the Birkat Hamazon?

The Birkat Hamazon (Grace after meals) is traditionally seen as the prayer for thanksgiving following any meal including the consumption of bread, or any meal that has been preceded by the saying of the Ha’motzi prayer (the prayer to thank God for the bread about to be consumed.)

Its Biblical origins are from the book of Deuteronomy, Chapter 8 Verse 10 – “V’achalta v’savata u’verachta et Adonai Elohecha al ha’aretz ha’tova asher natan lach” – “And you shall eat and be satisfied and then bless the Eternal for the land and the food that God has given us.” This was said by Moses whilst in the desert receiving the foodstuff known as manna, instructing the people to be grateful to God for providing them sustenance not just on a basic physical level, but also for sustaining B’nei Yisrael throughout time by giving them a land to dwell in as well.

However, we all know the Birkat Hamazon to be a much longer prayer than this simple sentence. This is because the prayer has multiple purposes and is sourced form multiple places, incidents and ancestral figures. The Birkat Hamazon is, in fact, a combination of four separate prayers:

- Birkat Hazan (which includes the Zimun – the invitation of the leaders of the prayer to the rest of the community.)

- Birkat Ha’Aretz – Begins with sentence “Nodeh lecha Adonai Eloheinu” and contains the quote from Deuteronomy regarding thanking God for the food and for the land itself.

- Birkat Yerushalayim – Begins from the sentence “Rachem Adonai Eloheninu al Yisrael Amecha, v’al Yerushalayim irecha.” This section claims its ancestral roots to our spiritual centre of Jerusalem.

- Birkat HaTov V’HaMetiv – This sections regards all that is good (tov and metiv being of the same shoresh (root) meaning “good”) and not only thanks God, but makes requests of God to maintain these good things. It is also the newest part of the Birkat Hamazon as it contains more of the modern prayers regarding the modern Sate of Israel and the situation of oppressed Jews in modern times, requesting God’s help, calling God “Harachaman” – The mericiful one.

Where does it come from?

The Birkat Hamazon, as stated earlier, is a lot longer than just the Biblical command to thank God for the food and land. The prayer is actually the work of a number of different authors throughout time.

The Textual Association

“When you have eaten your fill, you shall bless YHVH your God for the good land that God has given you.” (Devarim 8:10)

These words are the explicit source for the commandment of Birkat haMazon – blessing God after eating a meal. There are several blessings in the Birkat haMazon:

- HaZan – praise for God, who sustains the world;

- Birkat Ha’Aretz – thanks to God for everything, focusing on the Land of Israel;

- Boneh Yerushalayim – petition to protect and rebuild Jerusalem;

- HaTov vehaMeitiv – general praise and thanks for God.

In addition, when three or more people eat together, the Birkat haMazon is prefaced by the invitation known as Zimun. The Gemara (Berakhot 48b) expounds:

When you have eaten your fill, you shall bless – Birkat haZimun;

Adonai your God – Birkat haZan;

for the…land – Birkat haAretz;

…the good (land)… – Boneh Yerushalayim;

that God has given you – HaTov vehaMeitiv.

From this piece, it seems clear that all five of these blessings are sourced in the Torah. Although differing opinions are presented regarding HaTov vehaMeitiv and Zimun, the basic formula of the first three blessings is, according to all opinions, mandated by the Torah – D’Orayta.

The Historic Association

Earlier on that same page in the Gemara, we are told that Moshe composed the Birkat haZan when the Manna fell, Joshua composed Birkat ha’Aretz when the people entered the Land of Israel, David and Solomon composed Boneh Yerushalayim at different stages of the building of the city, and the Rabbis at Yavneh composed HaTov vehaMeitiv in response to the burial of the martyrs of Betar.

These two statements are apparently in conflict: From the first, it seems that at least three of the blessings are mandated by the Torah; from the second, it seems that these blessings were created at different point in history; such that at most, the first one was “in operation” at the time of the Torah, and the rest must be Rabbinic obligations.

One possible approach depends upon an understanding of form and text within the context of prayer. According to many Rishonim (see Rambam, Ch. 1 of Hilkhot Tefilla, Ramban’s comments on Sefer haMitzvot, Shoresh 1 etc.), there are several Mitzvot in the Torah which are presented in a most general way – and later generations (prophets, sages, custom) create, form and, eventually, determine specific texts through which these Mitzvot are fulfilled. For instance, according to several Rishonim (Rabbenu Yonah, Tosafot, Raavan), the Mitzvah of reading the Shema is essentially a Mitzvah of reading words of Torah – and the rabbis decided upon this particular text. According to Rambam, daily prayer – as mandated by the Torah – has only the most general form – praise, request and thanks. It was later rabbis (Ezra and his court) who formulated the specific blessings. (Other examples include Kiddush, Hallel (according to Ramban), teaching the Exodus to our children on Pesach night, confession on Yom Kippur etc.)

We can speculate the same here. The Torah commands us to bless God after eating by praising, thanking and beseeching God. The Torah itself not only provides no text for this blessing, it also provides no area of content.

When the Manna fell, Moshe composed HaZan, praising God for the kindness shown in sustaining the world. He not only composed this blessing, he also ordained that it be recited after every meal.

When the Torah was given, that blessing, along with the general blessings of (atopical and contentless) thanks and request, were the proper way to fulfill the command of Birkat haMazon.

When Joshua led the people into the Land of Israel, he “fixed” the “thanking” component to revolve around the Land. Clearly, the content of his blessing was different than ours, insofar as his likely included mention of the unfought battles for the Land. The third blessing was still a generic request.

When David built Jerusalem – and when Solomon constructed the Temple – they each “pinned down” a component of request (at that time it involved “protecting the city” – not “rebuilding it” as we request).

In summary, there were three stages in the development of Birkat haMazon:

- The Torah’s command, to praise, thank and beseech God after eating;

- The historical targeting of specific content areas for each blessing; (Moshe – praise for God’s sustenance; Joshua – thanks for the Land; David/Solomon – request for protection of Jerusalem and the Temple)

- The evolution of a (more or less) fixed text, after the destruction of the Temple.

As we praise, thank and beseech God after a meal, we also understand that by doing so we not only strengthen our connection with the Holy One, who is Blessed – but also with our history and our Land.